Don’t read this book on vacation. Save it for the time when you need a vacation but cannot break free of your routine. It would be a waste to read Ray’s prose ode to Georgia’s Altamaha River—“wide and made of molasses” (ix), one of the longest free-running rivers in the east—while otherwise charmed by exotic travel sites or lulled by carefree days on a beach or in the mountains. The book is too therapeutic to take on vacation; read it when you need it. Besides, on vacation, you might misplace it and not take it home to keep on your shelf, or, worse, not fully absorb its sweetness and wisdom.

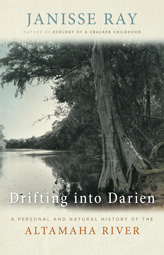

Janisse Ray, a passionate advocate for south Georgia, has brought public attention and affection to her homeland through her nonfiction and poetry. She has published three previous nonfiction books, most notably the bestselling and award-winning Ecology of a Cracker Childhood and a 2010 award-winning poetry collection, A House of Branches. In addition, she has co-edited several collections of nonfiction. Drifting into Darien is illustrated by the landscape photography of Nancy Marshall, which is at turns moody, unvarnished, and expansive, complementing Ray’s direct and personal prose.

Drifting into Darien unfolds in two symphonic movements played in legato. The first, “another camping-on-a-river story” (5) chronicles an eight-day paddle from the river’s origin at the confluence of the Oconee and Ocmulgee Rivers to its delta on the Atlantic coast. This first-person, present-tense account reveals how time spent floating and observing can restore a frazzled or frightened human mind to calm and balance. The second movement comprises vignettes, profiles, anecdotes, and feature stories that explore the river’s ecological value and challenges; its Native American, Spanish, and twentieth-century history; and the friends, acquaintances, and long-time associates with whom Ray has worked, and worried, and volunteered, and advocated to restore and protect the river, its floodplain, marshes, hammocks, forests, flora, and fauna. Some of these pieces lend themselves to anthologizing, most notably “Night Fishing with the Senator,” an amusing and poignant fishing trip with Ray’s state senator, Tommie Williams, “Sandhills,” a humorous account of an outing with botanists reveling in the impressive biodiversity of Big Hammock Natural Area, and “The Malacologists,” a lesson in river ecology featuring freshwater mussels and those who study them.

This structure layers sights, sounds, smells, people, events, and causes to show readers how full of quiet beauty and wonder this important, but relatively unsung river is: one of the world’s “75 Last Great Places” in the view of The Nature Conservancy. The book demonstrates how those who care about their home landscapes can make a difference in the health, use, and conservation of a place if they organize and collaborate over time as have the activists, fishermen, regular folks, academics, nonprofits, and government officials who have established the Altamaha Bioreserve. It takes decades, many people, and multiple, persistent, and ongoing efforts, readers learn, to protect almost 100,000 acres of land along the river’s 137-mile course, the bioreserve’s 2011 status (106). As Ray explains, “The story is one of the transformation that is possible if one wakes up to the beauty and wonder of the earth, if one fears not, if one follows the path of his or her heart. The story of the transformation possible if people join together and decide to protect something they love. With love, many things are possible.” (126)

Simultaneously, the two-part organization highlights Ray’s theme of vivid moments of experience that give our lives meaning. The week-long narrative provides many of these, as does the bounty of occasions and outings that have occurred throughout her life and are chronicled in the second part. One takes place on a moonlight trip when “a burden of moths” overwhelms a group of paddlers: “Moths were so thick they were like sparks from a house burning. Someone had called roll and all the nocturnal moths in south Georgia had answered. Along the river hundreds of thousands of them hit the water and lay there, drifting, surrendering to the mouths of fish. We must be out in a hatching, I thought” (57). In the book’s last pages Ray explains why such instances need to be shared: “history is interesting, but I think what matters most is this moment. This moment of the river matters to me, and it matters to you because this is a moment I am living for you. This is a story I am writing for you, full of moments that are also yours. Wherever you are, on your river, the moment matters.” (220)

The book’s title fittingly recalls the final lines from an 1816 John Keats sonnet, “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer”:

Or like stout Cortez when with eagle eyes

He stared at the Pacific—and all his men

Looked at each other with wild surmise—

Silent upon a peak in Darien.

This poem casts Keats’ astonishment when reading a new translation of Homer in terms of a conquistador “discovering” the Pacific Ocean. Ray’s choice to title her book using the name of an inland town, Darien, rather than a place located directly on the coast such as Wolf, or Egg, or Little St. Simons Islands, provides accuracy because the paddling group from part one selected Darien as its take-out point. But it also suggests that “seeing” the Altamaha is equal in wonder to Balboa’s (not Cortez’s) first view of the Pacific and, perhaps, to a new translation of an epic poem. Certainly Ray offers readers a new understanding of her beloved river. The connection is strengthened when we remember that Darien, Georgia, was named by Scotsmen who founded the settlement and used the occasion to commemorate the lives of relatives who had made a failed seventeenth-century expedition to the Isthmus of Darien (known now as the Isthmus of Panama), which is bordered in the south by the Darien Mountains, the peak from which the Pacific is seen in Keats’ sonnet.* Though it offers slow enchantment rather than an instant rush, readers of Ray’s prose will experience delight equal to the awe inspired by a new vista.

*“Darien History” City of Darien, Georgia. City of Darien: 2008. Web. 30 May 2012.

Beth Giddens is professor of English and Coordinator of American Studies at Kennesaw State University in Georgia. She received her Ph.D. from the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, in English with a specialty in rhetoric and composition. Recent publications include “Encountering Social-Constructivist Rhetoric: Teaching John McPhee’s Classic in an Environmental Writing and Literature Course” in Teaching Ecocriticism and Green Cultural Studies (Palgrave McMillan, 2011), “Saving the Next Tree: The Georgia Hemlock Project, Community Action, and Environmental Literacy” in Community Literacy Journal (Fall 2009), and “’Something Unusual in Hotel Accommodations’: Visiting the Smokies Early in the Twentieth Century,” in Smokies Life (Fall 2010).