William Ferris has poured his life’s work into this volume of interviews, photographs, and recordings with 26 writers, scholars, musicians, photographers, and painters who are as haunted by the South as he is. Ferris spent over 40 years gathering the material that makes up The Storied South, and the result is an intimate collection of insight into the lives and work of these icons, as well as a testament to Ferris’s significant role in the preservation of Southern culture.

A Mississippi native with a Ph.D. in folklore from the University of Pennsylvania, Ferris co-founded the Center for Southern Folklore in Memphis and served as its director for twelve years before establishing the Center for the Study of Southern Culture at the University of Mississippi. He served as director there, as well as a professor of anthropology, until 1997, when President Bill Clinton appointed him chair of the National Endowment for the Humanities. After leaving the NEH, he took his current professorship at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and became the Senior Associate Director of the Center for the Study of the American South. He’s written or edited ten books, including the hefty Encyclopedia of Southern Culture.

In his introduction to The Storied South, Ferris writes: “The story is the inescapable net that binds southerners together.” He cites the region’s “powerful sense of place,” as well as matters of both class and race as critical components of the “southern memory.” In each of the 26 instances, he begins by recounting his personal relationship with or impression of each interviewee then lets his subjects talk. Rather than utilizing a question and answer format, Ferris has shaped the interviews into fascinating first-person narratives.

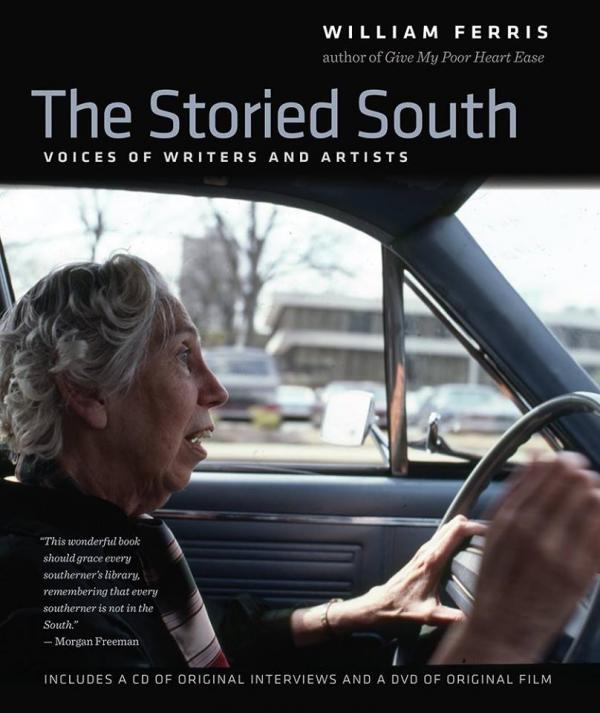

Eudora Welty tells Ferris about the time she went sailing with William Faulkner on man-made Sardis Lake in Oxford and about growing up in a house where learning was valued: “We were brought up with the encyclopedia in the dining room, always jumping up from the table to settle an argument and look up things in the unabridged dictionary and haul out the atlas.” (29). Welty also comments on the importance of place to her work:

Sense of place defines things for me and fills me with a sense of history. I cannot imagine writing without the base of place, any more than I can imagine writing without the other things a writer needs to make his story valid both to himself and to the readers. In the South, we have an inherited identification with place. It still matters. Life changes, as it always will and should. But I think the heritage of place is too important to let slide away. (35)

Ferris offers us other gems from his subjects. From Ernest Gaines: “I left the South when I was quite young because I could not get the kind of education my people wanted me to have there. I still write about the South because I left something there. I left a place I could love.” From Robert Penn Warren: “My father was full of poetry.” From Alice Walker: “When I was eight or nine or ten, I began to write, and I kept a notebook. My life has had its trials. I learned very early that writing was a way to deal with pain and isolation.” From photographer Walker Evans: “I am in love with civilization.”

The visual artists Ferris includes in the book are also gifted wordsmiths. Abstract painter Sam Gilliam says:

When I came back to visit Louisville, I knew I was home when I first saw the river. There may have been twenty-five or thirty miles to go still, but the excitement was to drive along and watch it. It would give me the feeling of being wed to land and spirit, all of which is caught up with one’s memory about a place.

Sculptor Ed McGowin discusses the nature of the Southern story:

The southern verbal tradition as it relates to visual arts is heavily loaded with a surreal, ironic, macabre view of the world. This is particularly evident in southern stories-a la Faulkner-that you hear when you sit around and talk. You tell tales that have a magnificent climax. In other cultures, you might speak in one-liners. But in the South, stories go on and on and on, at great length and very slowly (208).The Storied South is a book you could read on and on and on; the CD, DVD, and photographs, lagniappe that helps the reader link names with faces. In the book’s conclusion, Ferris touches on the growing field of Southern studies and says about the voices in the book: “Their stories are the water in which I love to swim, and their literature and art are drenched in it.” The Storied South practically drips with their eloquence.

* * *

Kathleen Brewin Lewis is senior editor of Flycatcher.